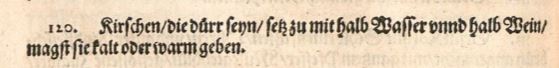

|

| Gelyne in Dubbatte |

As discussed in my previous post,

Henne in Bokenade, chicken is one of the most universally known animal food sources worldwide. All chickens can trace their roots back to the Red Junglefowl. The Romans introduced the bird to England during their occupation, and were experimenting with methods to feed and quite possibly breed them to produce heavier birds. It was also discovered at this time that castrating roosters would produce birds that were larger, tenderer and better flavored.

"Sacred Chickens" were raised by priests during this time period and were used for omens prior to significant undertakings. Priests would watch as the sacred chickens ate grain, if the chickens were stamping their feet and scattering about then the outcome would be favorable. However, if the chickens refused to eat then the undertaken was abandoned, as the outcome was not favorable. There is a

story I came across while doing research for this article that I found of interest.

When Claudius went to sea, he brought a flock of sacred chickens with him. When he needed a sign, a chicken would be killed and its liver inspected. A healthy liver was a favorable sign; a diseased liver suggested it was not a good time to risk a battle. The chickens were refusing to eat and this worried the men with Claudius. Their continued refusal angered Claudius and he threw all the chickens overboard with the comment (so the story goes), "If they won't eat, let them drink." The battle was lost because the gods did not favor the Romans - or because the men were convinced they were not intended to win and thus did not fight with all their will...

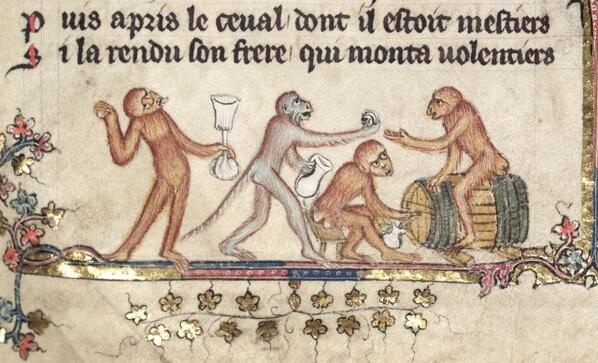

Medieval people enjoyed a varied diet, including goose, pheasant, quail, partridge, ducks even peacocks! Cockfighting was a favored sport, and the Old English Game Fowl became popular. Other breeds of chickens outside of the Dorking and the Old English Game fowl that survived medieval times include the Nanking, Poverara, La Fleche and the Minorca.

On farms, chickens were kept in domed structures made of wattle and daub, or, lean-to like buildings next to grain storage areas. Sometimes, they would share space inside of dovecotes. They were allowed to eat small insects and rodents in addition to a diet composed of wheat, beans oats and lentils. The best chickens were those that were avid egg layers. Chickens sometimes were used as a form of currency!

One of the major differences between modern chickens and chickens known in period would be the egg laying capacity. Modern chickens grow quickly, and can produce up to 300 eggs a year. Most modern birds are slaughtered when they reach 20 weeks of age. Their counterparts would produce approximately 40-60 eggs per hen, per year. While they age of slaughter varied, the average bird would live more than a year, and some of them were allowed to live four or more years.

Caponization, the act of castrating roosters is now considered inhumane in many areas which is why it is difficult to find capon. Pullets were caponized anywhere between 1 1/2 and 5 months. The process involves making a cut into the bird near the ribcage and removing the testicles. Unlike other animals, it is difficult to locate the testicles because they are not external, but internal, tucked up next to the spine. There are almost always losses during this process. In fact,

one record indicates that 30 out of 82 pullets died during the process of castration in 1375.

The next recipe I interpreted from

Two fifteenth-century cookery-books. Harleian ms. 279 (ab. 1430), & Harl. ms. 4016 (ab. 1450), with extracts from Ashmole ms. 1429, Laud ms. 553, & Douce ms. 55" Thomas Austin was Gelyne in Dubatte. This dish is quite delicious featuring chicken cooked in a mixture of broth, wine and spices, thickened with bread crumbs. This dish also resulted in another "dual" amongs the taste testers. One disappointed tester stated "I only got one bite!" while the victor literally stood in a protective stance in a corner eyeing everybody while eating.

.xlj. Gelyne in dubbatte. — Take an Henne, and rost hure almoste y-now, an choppe hyre in fayre pecys, an caste her on a potte ; an caste J^er-to Freysshe broj^e, & half Wyne, Clowes, Maces, Pepir, Canelle, an stepe it with fe Same broj'e, fayre brede & Vynegre : an whan it is y-now, serue it forth.

The interpretation below came from Dan Myers' "Medieval Cookery" site. If you have not had the opportunity to visit this site, you should :-D

xlj - Gelyne in dubbatte. Take an Henne, and rost hure almoste y-now, an choppe hyre in fayre pecys, an caste her on a potte; an caste ther-to Freysshe brothe, and half Wyne, Clowes, Maces, Pepir, Canelle, an stepe it with the Same brothe, fayre brede and Vynegre: an whan it is y-now, serue it forth.

41 Gelyne in Dubbatte - Take a hen, and roast almost enough, and chop her in fair pieces, and caste her on a pot, and caste thereto fresh broth and half wine, cloves, maces, pepper, cinnamon, and step it with the same broth, fair bread and vinegar: and when it is enough, serve it forth.

Interpreted Recipe Serves 1 as a main, 2 as a side if they are friendly!

1 bone in, skin on chicken breast

1 cup chicken broth -or- as an alternative water with 1 chicken bouillon cube dissolved in it

1/2 cup of wine (I used white, but I suspect red would be just as good and would render this dish very similar to Coq au Vin)

2 cloves

1/8 tsp. mace & pepper

1/4 tsp. ground cinnamon

3 tbsp. bread crumbs

1 tsp. white or red wine vinegar

Salt and pepper to taste

Use your best method to roast your chicken breast, but don't cook it all the way through, make sure it is a little under done. I cooked mine unseasoned in the oven at 375 degree's with just a little bit of olive oil for about 30-35 minutes (if you want your breast completely done, roast for at least 45 minutes). Alternatively, you could boil your chicken in the stock or water and bouillon mix until tender, then remove from stock, strain it, and then move forward from here while the chicken is cooling.

Add your wine, cloves, mace, pepper and cinnamon to your stock and heat on low. While the broth is heating remove the skin and bones from your chicken and cut your chicken into bite sized pieces. Once the broth has heated for approximately 15 minutes, remove the cloves, and slowly stir in your bread crumbs 1 tablespoon at a time. If the bread clumps your sauce will get chunky and that's not pleasant. Trust me! Stir in the vinegar, and keep your broth on low heat until it thickens to your desire. Mine was the consistency of a thin white sauce.

Strain your broth to remove any chunks of bread that might still be present then add the chunked chicken. Cook until chicken is cooked through and tender, the sauce will thicken a bit more. Serve!

This is another dish that can be as brothy or thick as you please. While bouncing ideas off of a friend of mine, we thought that rice flour added to this dish as a thickener in lieu of bread crumbs would also be a good thing, although it changes the recipe from the original, it would then make this recipe a gluten free alternative and still be within period as rice flour, was used as a thickening agent as well as eggs. This is another recipe for the "must serve at future events" list. This list, I fear, is going to become as long as my bucket list!

|

| Red Junglefowl |